Sign in

Don't have an account with us? Sign up using the form below and get some free bonuses!

Yesterday, there was a mass shooting very close to where I live. How's that for the beginning of a blog post?

This is not the kind of thing that should ever happen under any circumstances, but when it does, our lives can be deeply affected. As such, we need to be able to talk to our children in ways that are honest and supportive, but without going "too far." After all, they're still kids.

Let me preface this by saying that these tips apply to other hard situations, too. Anytime there is a loss, anytime there's something hard that's going on in the child's life, the discussion and healing processes are largely the same.

Perhaps it's the loss of a loved one or a pet. Perhaps it's something else that's a big deal emotionally -- whatever it is, it matters deeply to you or your child.

The shooting, of course, is particularly poignant right now because of what happened here yesterday.

We can feel really overwhelmed, ourselves. Of course, we have to start with our own processing; our own beginning of the healing process. We want to be careful not to just blurt out the news to our child.

We don't need to invite our child into our own processing, because by definition, as adults, we are going to process things differently than they do. We are going to have a different perspective than they will; different fears and concerns than they will.

Our first task is to pause, reflect, absorb, and decide how we want to respond. We must be very intentional about how we want to handle the situation with our children instead of reacting without thinking it through.

Related: FREE parenting and child development expert interviews

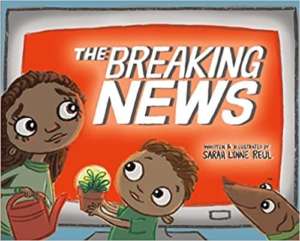

We know that kids talk to one another. We also know that many kids have access to screens and media and all sorts of sources of information that are not us.

We don't know what those sources are going to share. We don't know if they are going to be accurate. And we certainly don't know if they are going to be age appropriate.

We want to handle the situation in a way that's appropriate for our child, specifically. There is no one size fits all. There is no script that works for every child.

Whenever possible, we wand to be the first one to share the news with them. Obviously, sometimes kids hear things before we do, and if that happens, our job is to be emotionally safe; be responsive to our child.

We want to hold space for the their feelings and talk about the things we need to talk about in ways that resonate with our family values, with our belief systems, with the messages that, once again, we know are appropriate for our children.

To be clear, I say "appropriate for our children" in very loose terms because there is nothing "appropriate" about tragedy.

I do believe in being direct with children. However, depending NOT only the age, but more so depending on the emotional maturity of the child -- as well as what they are likely or unlikely to hear from other sources -- you want to be age appropriately honest.

For example, if it is something like the tragedy that was the mass shooting yesterday, you can say to a young child, "Something really terrible happened. Somebody came into a place and hurt a whole bunch of people." You can leave it at that. They don't need more detail.

You can then move forward to next steps; how we're going to take care of ourselves and each other, and how we're safe and everybody we know is safe (if that's true).

For an older child, you might share more information. Perhaps they're old enough to know the location of the incident without developing a fear of all places of its kind. You know them best.

As I mentioned above, the same approach can. be effective for other tough situations.

For example, if a grandparent died, a younger child might only need to know that they're gone and how very much they were loved.

An older child might understand more detail of a long-term illness, for example, and how that illness is different from the common cold or flu.

You can share your family's belief system around the event and then move forward, compassionately, with extra love and support as you navigate the loss.

"In the moment" -- while you're discussing the situation -- you can adjust the amount of detail you share based on your child's sensitivity, their emotional maturity and their body language, and their responses to what you're saying.

Keep in mind that some kids are "processors" and won't show their true response right away. Go slowly.

For the children that can only handle the details and bite-size pieces, they might know that something bad happened, but that's enough for right now.

If they ask, "Can we talk about this later?" Your answer can be, "Yes, of course." Trust your chid's timing and cues, verbal and non-verbal.

We don't need to divulge everything that's on our heart. We need to trust the child in front of us. Revisit what you need to, later.

Some children, of course, really want to hear more details.

Related: Positive parenting mini-courses

It is entirely misleading to the child if we put on a brave face and act like we are unaffected by big events.

We need to be authentic.

We need to say things like, "I am so sad that this happened."

"I am so angry that this happened."

"I am so --" whatever you are feeling. It's all valid.

In being emotionally authentic, you are modeling to your child.

It's also important to let your child know that you're responsible for your own feelings, and even though you are feeling sad or angry (or whatever it is you're feeling), that you're going to find ways to deal with these feelings. It's not your child's job to "fix" them.

Be specific about how you're going to support yourself. You might say, "I'm feeling really sad about this situation, so I'm going to:

The child needs to know that addressing your feelings is your job and you've got it under control, even if it's hard right now.

Encourage them. Offer emotional safety to them.

Mr. Rogers always said we should "look for the helpers," and I firmly believe that this is instrumental in our healing from everything hard that happens in life.

If it's a medical situation, we can express gratitude for the medical facilities and personnel that are out there helping every single day. Even when nothing difficult is happening, they're still there and they are prepared.

We might share hope that stems from our faith.

We might share hope in gratitude that we are alright, or in something specific we can do to be part of others' healing.

Share whatever gives your child hope that life goes on, that things will get better. Let them know that time helps all wounds, because it truly does. It may not heal them fully, but it always helps once time has passed.

Lest I sound cliché, I want your child to know these truths. They're not "toxic positivity," because we're not pretending things are easy. We're not gaslighting or glossing over anyone's feelings. No one would "buy it" if we said everything was alright in the first place. Sometimes, things just aren't okay.

Share the specific and actionable steps that we can take right now, in this moment of hardship, to give us hope -- to give us that olive branch -- to give us something to hold on to.

These things will carry us through until we get to a place of peace and emotional safety again.